|

Early Period (Mid 7th - Mid 9th

Century)

The most characteristic of the early Cham art is the

collection of sculptures from My Son (outside of Da Nang), the most

venerated temples in ancient Champa. This group of sculptures marked

the golden age for Cham culture, even if this culture was influenced

by pre-Angkorian Khmer art. A century later, when the leadership of

Champa passed to the southern provinces, artistic activity seems to

have declined. It was at about this time that the Indonesian

attacked on the peninsula stimulated the growth of Buddhism in

Champa and revitalized its iconography.

|

|

The Period of Indrapura (Mid 9th to End

of 10th Century)

Around the year 850, power once again passed to the northern

provinces and for a century and a half Indrapuri (Dong Duong in

present Quang Nam province) was the capital of the Cham kingdom.

Though typified by two quite opposite tendencies, the period was one

of intense artistic activity. As early as 875, the founding of the

great Mahayana (Dai Thua) Bhuddist complex at Dong Duong

led to the embellishment of a vigorous style that was much more

concerned with grandeur than with human beauty, and yet welded

together with a surprising degree of originality the most varied

borrowings from Indonesia and China. A quarter of a century later,

with the decline of Buddhism, sculpture became progressively more

humane and decoration more delicate (Khuong My). When, towards the

middle of the 10th century, architecture achieved a classical

balance (My Son, group A), sculpture moved into its second golden

age with the style of My Son A1 and Tra Kieu which shows a strong

Indonesian influence. By the end of the 10th century, when the

kingdom engaged in hostilities with a now independent Viet Nam, its

art had already lost many of its finest qualities, especially with

regard to the rendering of the human figure.

|

|

The Period of Vijaya (11th to End

of 15th Century)

As

result of attacks by Vietnamese forces, Indrapura, which lay to far

to the north, was evacuated in favor of Vijaya (Cha Ban in the

present Qui Nhon city), a capital further to the south. Even though

the kingdom was threatened from all sides, Vijaya was to witness

much artistic activity during the 11th and 12th centuries. Growing

tension between Khmer (Cambodia) and Champa led to the introduction

of some new borrowings

from the Khmer art; however the worsening of political relations

culminated in the occupation of Champa by forces from Angkor (1181

to 1220). All Cham artistic activity ceased, and the kingdom was to

emerge much the poorer from the experience. Once set in motion, the

decline was accelerated by the invincible onslaught of Viet Nam, and

then, at the end of 13th century, by the Mongol threat. The few

buildings erected in the 15th century in the less harassed regions

are of heavier proportions and became progressively less and less

ornamented (Po Klong

Garai).

|

|

Late Period (After

1471) Late Period (After

1471)

This period

began with the capture of Champa's capital of Vijaya by the

Vietnamese. Po Ro Me temple, probably built in the 16th century, was

the last sanctuary of the traditional type. Those that followed it

(the bumongs of hybrid construction) were to be influenced by

Vietnamese architecture. Religious images became mere steles (kut)

which are characterized by the progressive effacement of the human

physiognomy, until only attributes of rank (especially head-dresses)

remains as a reminder of them. Yet although these sculptures reveal

a continuos decline, they do manage to retain something of the

profound originality that is the only truly constant feature of the

art of Champa.

Kut in human shape, sandstone,

17th century, Thanh

Hieu.

| |

|

|

Cham Sculpture

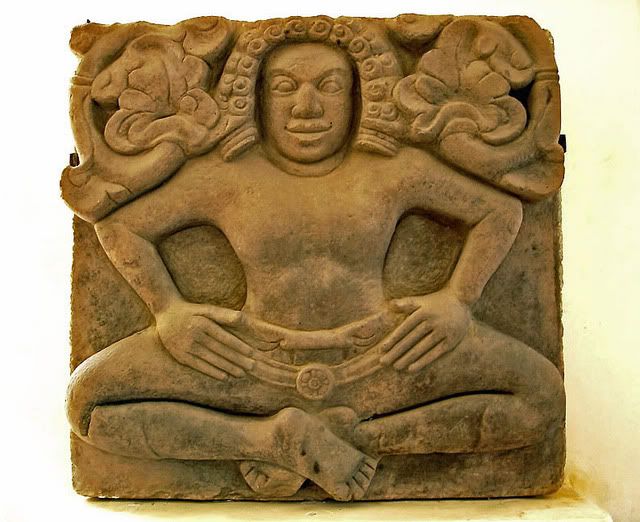

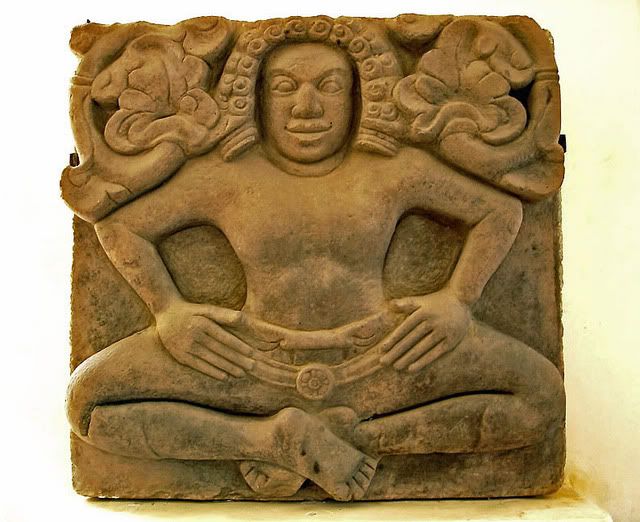

Cham

sculpture, unlike the architecture that is conservative in its

design and methods, is marked by continual changes, reflecting new

influences rather than a natural evolution. Although it can not be

denied that there were occasions when Cham art reached heights of

pure, classical beauty (such as the My Son and Tra Kieu

temples), sculptures for the most part to have expressed

contradictory tendencies: conventionality and innovation, a lack of

decorative details and an excess of it, both realism and fantasy.

There is more and more an aversion to sculpture in the round until,

finally, carving in high relief became the only means of expression,

and a certain disregard for natural poses resulted in a loss of

balanced proportions. It should be stressed that, in view of the

constant and profound changes in Cham art, it is the study of

costume, hairstyle, and above all, personal ornaments that give the

most reliable stylistic evidence for dating sculpture.

Apsara dancer, sandstone pedestal from Tra Kieu, early 10th

century | |

|

In spite of the fact that sufficient

examples of bronzes and terra cotta have survived to demonstrate

that these two techniques were important at all times, too many have

been destroyed for us to be able to trace their development

satisfactorily. Some detachable ornaments from idols (head-dresses,

bracelets, necklaces, etc.) of chased

gold or silver dating from the end of the 9th century or the

beginning of the 10th have been found. The only other known

ornaments (the regalia of Cham kings) are not earlier than the 17th

century. The visual evidence relating to personal ornaments in the

intervening period is limited to that provided by sculpture. In spite of the fact that sufficient

examples of bronzes and terra cotta have survived to demonstrate

that these two techniques were important at all times, too many have

been destroyed for us to be able to trace their development

satisfactorily. Some detachable ornaments from idols (head-dresses,

bracelets, necklaces, etc.) of chased

gold or silver dating from the end of the 9th century or the

beginning of the 10th have been found. The only other known

ornaments (the regalia of Cham kings) are not earlier than the 17th

century. The visual evidence relating to personal ornaments in the

intervening period is limited to that provided by sculpture.

Royal Tiara, Gold, 17th century.

|

|

| |

| Hinduism had profound influence on the ancient art of Champa

and inspired many sculptures that decorate the Cham's temples and

towers. These statues and bas-reliefs were carved from stone or made

of terra-cotta after figures of god and mythical animals from the

Brahman religion. The three divinities worshipped by the ancient

Cham people are:

Brahma is the Creator who is continuing to create new

realities. Brahma has four arms and four faces (represent East,

West, North and South). His wife is Saravasti. Brahma is usually

displayed riding on the sacred goose of Hamsa.

Shiva, the Destroyer, is at times compassionate, erotic and

destructive. He symbolizes all the violence and forces in the

universe. Shiva has a third eye in his forehead. and can have many

arms and faces. Shiva has many wives, among them Parvatti, the

goddess of Earth, Uma, the goddess of grace and Durga, the

goddess-combatant. Shiva is sometimes displayed riding the sacred

bull of Nandin Vishnu, the Preserver who preserves these new

creations.

Vishnu has one face and four arms, each arm holds a disc, a

horn, a ball and a club. His wife is Laksmi, the goddess of beauty.

Vishnu is usually displayed riding Garuda, the mythical creature of

half-human and half bird.

Other religious figures found on the ancient Cham sculptures

are Ganesa-the god of intelligence, Indra-the god of the rain,

Kama-the god of love, apsara-the celestial dancers and naga-the

multiple-head serpent, the founder of the dynasty.

Minh

Bui

References: Forms and

Styles of Asia-Champa, Prof. Jean Boisselier, 1994

|

|

Cham

architecture is essentially an architecture of bricks.

The bricks were of excellent quality, and after being rubbed

smooth, were bonded by means of a mortar of vegetable origin,

thereby rendering the joints almost invisible and producing

surfaces that readily lent themselves to sculptures.

Po Klong Garai tower, Binh Dinh, late 13th

century

With the exception of

the temple of Dong Duong (AD 875), Cham architecture does not

have buildings of the grand scale of those found in Java or

Cambodia. Cham temples usually consist of a sanctuary tower

(the kalan) together with a few smaller outbuildings. At many

temple sites, one can find an assemblage of buildings dating

from different periods.

The Chams used only

two methods of roofing their temples: courses of corbel bricks

for covering small areas, and tiles on a timber framework for

larger buildings. As a rule, the sanctuary towers are

characterized by a relative lack of embellishment as well as

by their graceful proportions. These square buildings derive

their proportion from their pilaster and projections and

usually have a large entrance hall. The high roofs consist of

progressively smaller stories, forming the basic shape of the

building. Apart from the occasional lodge and small temple

with the layout similar to that of the kalan, the secondary

buildings are of two types: the 'library' of oblong shape,

most frequently comprising two rooms under a curved roof of

corbelled bricks, and the 'hall', a larger building with

thinner walls pierced by balustrade windows. The halls have

roofs of tiles on a timber framework and are sometimes divided

by massive pillars into three naves. The decoration of these

buildings normally takes the form of carved relief on brick,

but for the decoration of sanctuaries, tympana, metopes,

antefixes and certain other features, carved sandstone was

generally used.

Major Cham Monuments

My Son Towers

My Son,

which is located outside of Da Nang, is the most important

Cham site in Viet Nam. During the centuries when Simhapura

(Tra Kieu) served as the political capital of Champa, My Son

was the most important Cham intellectual and religious center

and may also be served as the burial place for Cham monarchs.

My Son is considered to be Champa's counter part to the grand

cities of South-East Asia's other Indian influenced

civilizations such as Angkor (Cambodia), Pagan (Myanmar),

Ayuthaya (Thailand) and Borobudur (Java). My Son became a

religious center under King Bhadravarman in the late 4th

century until the 13th century, the longest period of

development of any monument in South-East Asia. Most of the

temples in My Son were dedicated to Cham kings associated with

divinities, especially Shiva, who was regarded as the founder

and protector of Champa's dynasties. The monuments at My Son

have been classified by archaeologists into ten main groups

lettered from A to K according their style and period where

the buildings were constructed. Many of the My Son towers were

destroyed or severely damaged during the Viet Nam war in the

60's.

Simhapura (Tra Kieu)

Also

located outside of Da Nang is Simhapura, the Lion City, the

first capital of Champa, serving its capacity from the 4th to

the 8th centuries. Today, nothing remains of the city except

the rectangular ramparts. A huge number of Cham artifacts,

including some of the finest carvings are found from this

site. | |

|

|

Indrapura (Dong Duong)

The

Cham religious center of Indrapura was the site of an

important Mayahana Buddhist monastery, the Monastery

of Lakshmindra-Lokeshvara. Indrapura served as the capital

of Champa from 860 to 986 until the capital was moved south to

Vijaya (Cha Ban near Qui Nhon).

Po Nagar Towers

Located outside of Nha Trang, the Po

Nagar (the Lady of the City) towers were built between the

7th and 12th centuries on a site used for Hindu worship as

early as the 2nd century AD. There were once seven or eight

towers at Po Nagar, four of which remain. At the site there is

a mandapa (meditation hall) where worshipers must pray before

proceeding to the kalan (sanctuary). The 23-meter high North

tower, with its terraced pyramidal roof, vaulted interior

masonry and vestibule, is a superb example of Cham

architecture. It was built in 817 by King Harivarman I , 43

years after the original temples were sacked and burned by

Indonesian corsairs.

Po Klong Garai Towers

Located in Phan Rang province, the Po Klong

Garai site consists of four brick towers constructed at

the end of 13th century during the reign of King Jaya

Simhavarman III.

Po Ro Me Towers

Also

located in Phan Rang is the Po Ro Me, one of the newest Cham

tower. The tower is named after the last ruler of the

independent Champa, King Po Ro Me (ruled 1629-1651) who died a

prisoner of the Vietnamese.

Minh

Bui

References:

Forms and Styles of Asia-Champa, Prof. Jean Boisselier,

1994

| |

|